DREAM: Camera Calibration without Fiducial Markers through Sim2Real Keypoint Detection

This post describes an approach to camera calibration without fiducial markers that combines deep-learning-based keypoint detection with a principled, geometric algorithm to provide a camera-to-robot pose estimate from a single RGB image. Our approach is facilitated by sim2real transfer: we train our keypoint detector using only synthetic images. Our approach, which is detailed further in our paper published at ICRA 2020, is called DREAM: Deep Robot-to-camera Extrinsics for Articulated Manipulators. Our approach provides pose estimates that are comparable to classic hand-eye calibration, the standard in practice for camera calibration. Code, datasets, pre-trained models, and a ROS node for DREAM are publicly available.

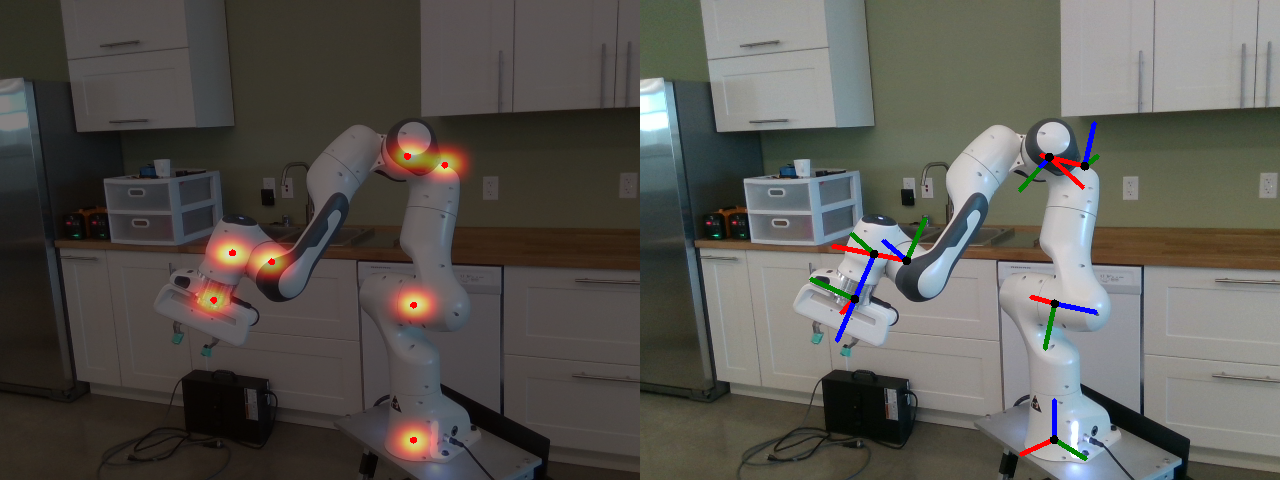

DREAM output for the Franka Emika Panda manipulator. Left: keypoint detections with belief map overlay. Right: DREAM as camera calibration. Keypoint frames are projected into the image using the camera pose estimate from DREAM.

DREAM output for the Franka Emika Panda manipulator. Left: keypoint detections with belief map overlay. Right: DREAM as camera calibration. Keypoint frames are projected into the image using the camera pose estimate from DREAM.

An Overview of DREAM

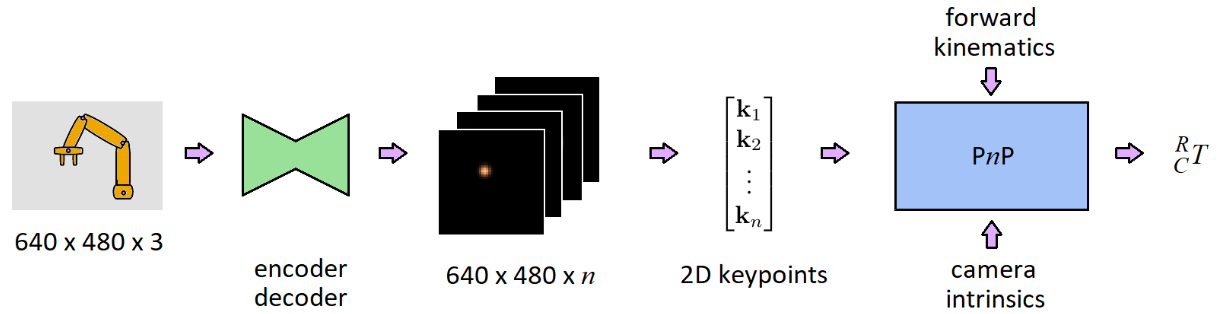

DREAM is a two-stage pipeline. The first stage detects keypoints of a manipulator in an input RGB image. The second stage uses the detected keypoints along with the camera intrinsics and robot proprioception to estimate the camera’s pose with respect to the manipulator. The first stage involves two-dimensional inference, whereas the second stage involves three-dimensional inference. Our work is inspired by DOPE: Deep Object Pose Estimation (Tremblay et al.).

The DREAM pipeline. Stage 1 consists of the first four steps shown in this diagram. Stage 2 is the last step, which outputs the camera transform.

The DREAM pipeline. Stage 1 consists of the first four steps shown in this diagram. Stage 2 is the last step, which outputs the camera transform.

DREAM is an approach that is enabled by deep learning while also leveraging classical algorithms. As an alternative to directly regressing to pose, such as in PoseCNN (Xiang et al.), vision-based geometry algorithms, such as perspective-n-point (PnP), provide a principled method for estimating pose from keypoint correspondences if the camera intrinsics are available, as in our case. Therefore, we need not apply deep learning to the entire pipeline to regress directly to pose, which has the risk of “baking in” the camera intrinsics and limits how well the algorithm generalizes to other cameras. Geometric algorithms do not have this problem and will transfer well to other cameras. (In fact, for our work, we demonstrated this for three different cameras.) Thus, we utilize deep learning where it excels — image detection — and the rest of the problem is thereafter solved using a geometric algorithm.

This post will largely focus on the first stage, and how we achieved sim2real transfer for keypoint detection using only synthetic data.

Stage 1: Keypoint Detection

This stage detects manipulator keypoints within a single RGB image. Keypoints are salient points defined on the robot that are useful for estimating the camera-to-robot pose. The engine that drives this stage is a deep neural network with an encoder-decoder architecture. The network is trained to output a belief map for each robot keypoint, which is then interpreted to determine the pixel coordinates of that keypoint in the input image. We will discuss this more thoroughly later in this post.

DREAM requires the keypoints to be specified by the user at training time. In our work, keypoints were chosen at the positions of the joints based on the robot URDF (Unified Robot Description Format) model. In this case, the number of keypoints will range from 7 to about 20, depending on the model. In principle, these keypoints can exist anywhere on the robot — including “inside” the robot, as was the case for the DREAM models that were trained for ICRA. Additional keypoints can be added to provide slightly better results in terms of accuracy (with diminishing returns) and robustness, particularly when some keypoints are occluded or otherwise not detected.

Stage 2: Pose Estimation from PnP

This stage estimates the camera-to-robot pose using the keypoints detected in the first stage. This pose is equivalent to , the transform that relates the camera pose to the robot pose. Finding this pose is equivalent to solving the camera calibration problem.

Essentially, this stage is framed as solving a Perspective-n-Point (PnP) problem. In other words, given the camera intrinsics and point correspondences (i.e., a set of image keypoints and their corresponding positions in three dimensions), find the camera pose which best explains these correspondences. We utilize the Efficient PnP (Lepetit et al.) implementation that is available in OpenCV plus a one-step refinement.

To solve this, we need (in addition to the detected keypoints) the camera intrinsics and the three-dimensional positions of the keypoints. For our work, we used the intrinsics as published by the camera in use. The three-dimensional positions of the keypoints are obtained from the robot forward kinematics.

Synthetic Data Generation

Deep learning requires data — lots of data. Fortunately, synthetic data are cheap, relatively speaking. Moreover, synthetic data provide exact labels for training a network. To transfer our keypoint detector to reality, sufficient training data are required with enough variation for the network to learn the salient signal within the input images to detect keypoints. We employ two common techniques for facilitating sim2real perceptual transfer: domain randomization and image augmentation.

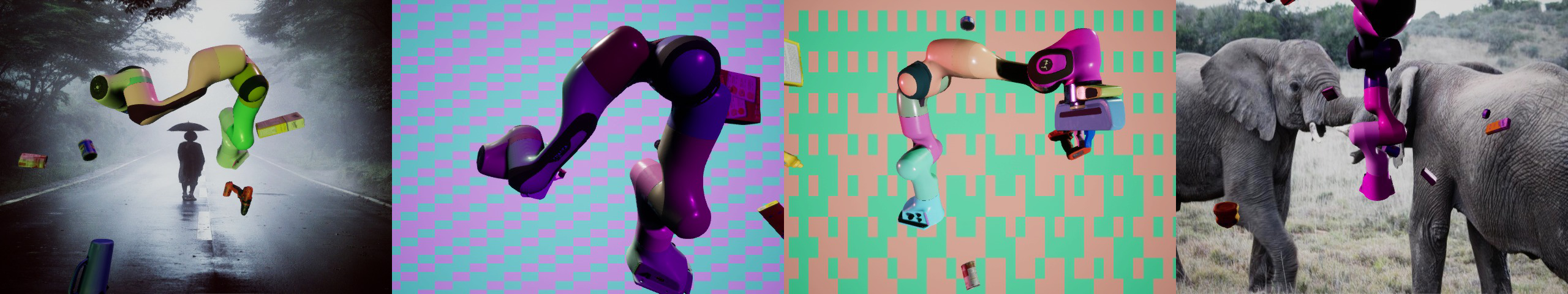

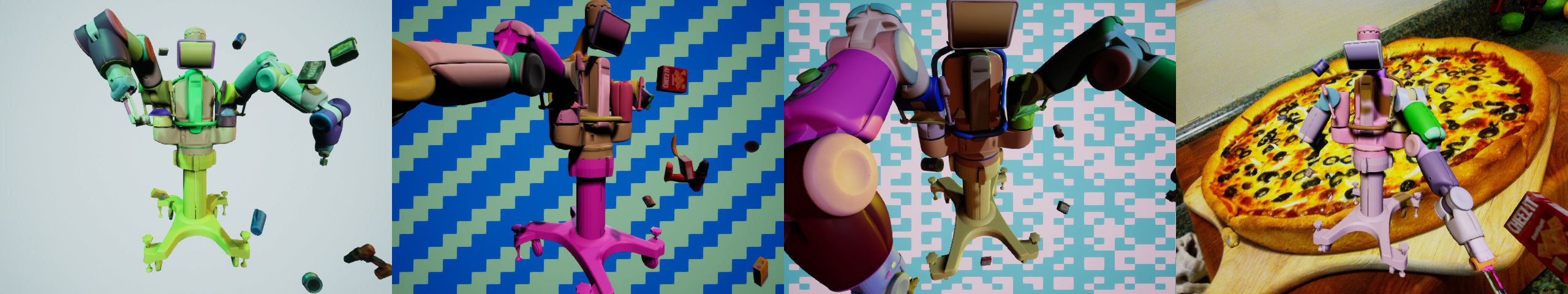

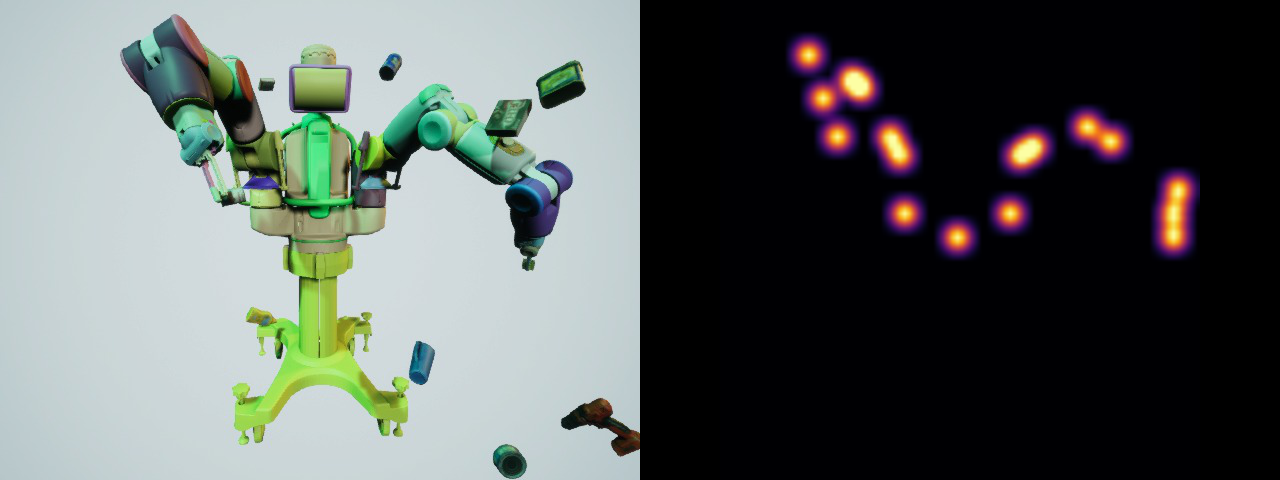

We added robot control to an internal version of NDDS, the NVIDIA Deep learning Dataset Synthesizer, to generate our training data. Below are some synthetic image examples from NDDS that are suitable for training the network.

Synthetic, domain-randomized images for the Franka Emika Panda, KUKA iiwa7, and Rethink Robotics Baxter manipulators.

Synthetic, domain-randomized images for the Franka Emika Panda, KUKA iiwa7, and Rethink Robotics Baxter manipulators.

Domain Randomization

Broadly speaking, domain randomization changes the content of an image to provide a diversity of examples to facilitate generalization. For example, if the network only saw examples of the keypoints at the same robot joint configuration, we wouldn’t know if it could generalize to other joint configurations. To that end, we provided domain randomizations in factors that could reasonably change in real settings:

- The camera pose is randomly chosen within a hemispherical shell with the robot at the center. The camera view is slightly perturbed so that the robot is not always centered within the image.

- The robot joint configuration is randomly chosen. Specifically, each joint has a uniform angle distribution that is chosen independently for each joint. This, along with perturbing the camera view, means that some images will have keypoints that are outside the field of view.

- The lighting of the scene is varied in position, intensity, and color.

- The scene background is randomly chosen to be a pattern or an image from the COCO dataset (Lin et al.).

- Addition of distractor objects from the YCB dataset (Calli et al.).

- The color of the robot mesh was randomly chosen.

Image Augmentation

Image augmentation provides image-level noise to increase network robustness and generalization. Unlike domain randomization, the semantic content of the scene not changed in image augmentation. We use albumentations for our augmentations. Specifically, the following augmentations are applied to the training images:

- Gaussian white (zero-mean) noise for each pixel.

- Random adjustment to image brightness and contrast.

- Random translation, rotation and scaling.

Sim2Real Keypoint Detection

Network Training

Now that we’ve generated our training data, the neural network can be trained through supervised learning. We provide the network data samples consisting of the input data (RGB image) and the label it should output (one belief map per keypoint).

What should these belief maps look like? Similar to DOPE, the belief map for a keypoint is defined as a Gaussian intensity distribution at a given keypoint’s pixel location. If a keypoint is not in the field of view, the belief map label will be completely zero.

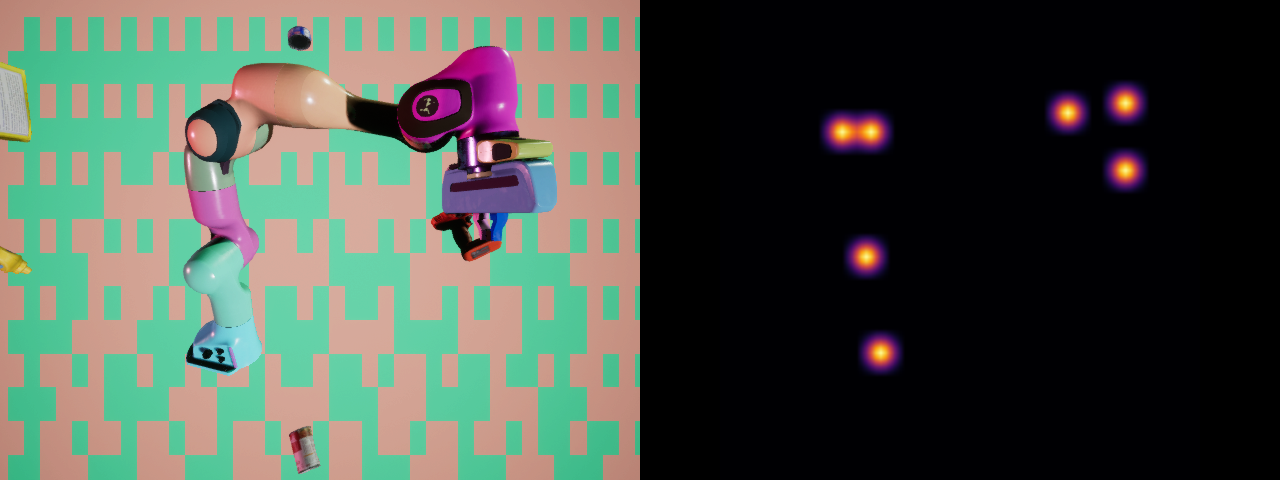

Below are some examples of training data for the selected robots. Our network also allows the belief map output resolution to be specified via the decoder resolution. The Panda and Baxter belief maps below are for a quarter “Q” resolution, whereas the iiwa7 belief maps use a half “H” resolution.

Training data examples for the Franka Emika Panda, KUKA iiwa7, and Rethink Robotics Baxter manipulators. Left: RGB image as network input. Right: keypoint belief maps (shown here as flattened) as network training label.

Training data examples for the Franka Emika Panda, KUKA iiwa7, and Rethink Robotics Baxter manipulators. Left: RGB image as network input. Right: keypoint belief maps (shown here as flattened) as network training label.

Network Inference: Interpreting Belief Maps

Although the network regresses to belief maps, PnP doesn’t operate on these belief maps directly. Instead, the belief maps are interpreted to determine where a keypoint is most likely to exist via a peak-finding algorithm. A key assumption in this step is that only one keypoint exists in a particular belief map. First, a Gaussian filter is applied to smoothen the belief map. Then, the intensity peaks that are above a heuristic threshold are identified. Lastly, if multiple peaks are detected, the relative intensity between the maximum and next maximum is compared; if this is above a threshold, the max peak is retained. If the peaks cannot be clearly disambiguated, no keypoint is detected. In practice, this has been effective in cases where only one robot is in the field of view.

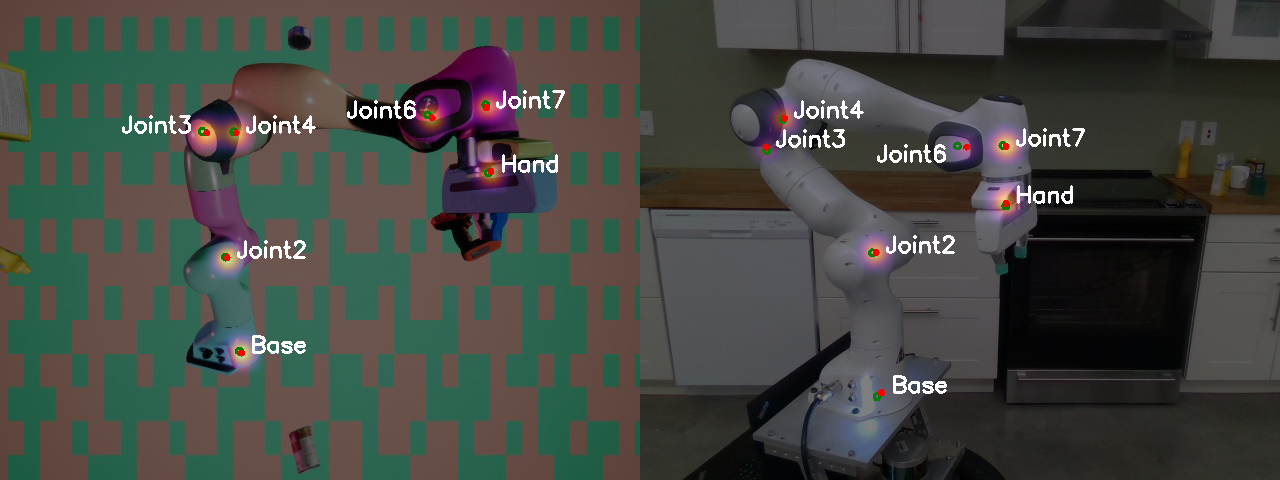

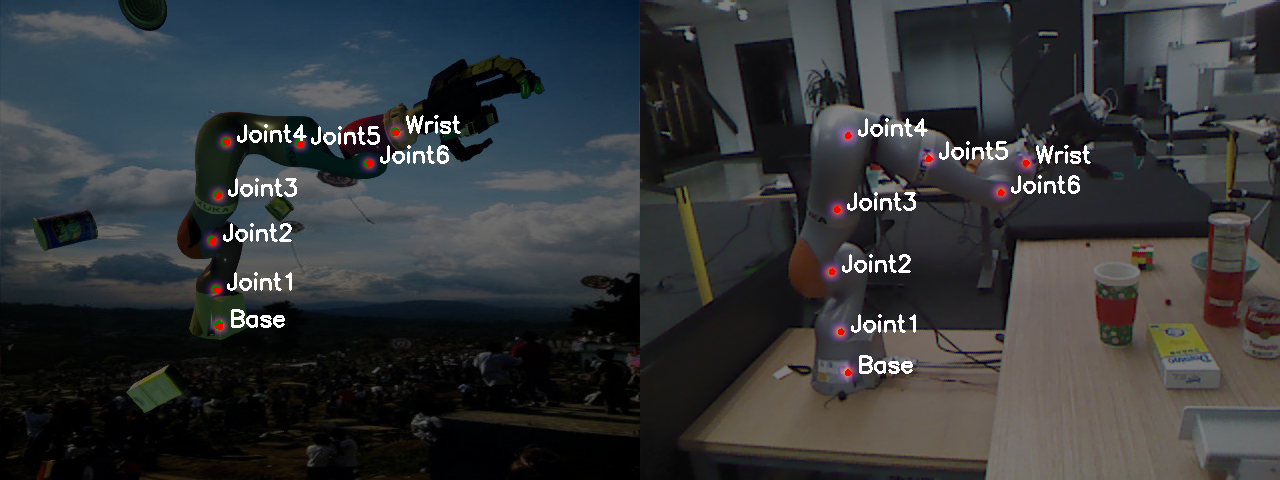

Below are examples of our trained keypoint detector for both synthetic and real images. The same network is used for both the left and right images, demonstrating sim2real perceptual transfer.

Sim2real transfer for keypoint detection for the Franka Emika Panda, KUKA iiwa7, and Rethink Robotics Baxter manipulator. Left: synthetic input image. Right: real input image. In both cases, detected keypoints (shown in red) were found from the overlaid belief maps. When available, ground truth keypoints are shown in green.

Sim2real transfer for keypoint detection for the Franka Emika Panda, KUKA iiwa7, and Rethink Robotics Baxter manipulator. Left: synthetic input image. Right: real input image. In both cases, detected keypoints (shown in red) were found from the overlaid belief maps. When available, ground truth keypoints are shown in green.

A DREAM for Better Camera Calibration

Below is a video from one of the real datasets we have released that demonstrates DREAM. Each frame of this video shows the DREAM keypoint detections as well as the projected keypoint frames using the DREAM camera pose estimate for the camera calibration transform. No temporal information is used; DREAM processes each frame independently. Therefore, if the camera were to have been moved or bumped during this sequence, DREAM could still provide a viable calibration solution, which would not be possible with hand-eye calibration. In our paper, we demonstrate that the camera transform from DREAM is comparable to classic hand-eye calibration, therefore suitable for grasping objects that require no more than 2-3 cm of error.

Closing Thoughts

Lessons Learned

Transferring robot perception algorithms to reality using only synthetic images is difficult. We provide the following lessons learned for other researchers.

-

Photorealistic textures. It comes as no surprise that photorealistic models will better facilitate sim2real transfer. However, recall that in our synthetic training data, the color of the robot textures were changed. Some perceptual differences should be fine, so long as they don’t change the underlying perception content (e.g., the shape of the manipulator links). For example, the Panda robot has an LED at its base to indicate its operating mode. This LED was not modeled by our renderer, but nonetheless, the keypoint associated near it (at the base) was still detectable.

-

Judicious restriction of domain randomization. If the expected use case of the robot is restricted, then it is reasonable to also restrict the degree of domain randomization accordingly. For example, the workstation of the Baxter robot is in front of its torso. We restricted the camera pose randomization so that only the front of the torso was visible. Limiting the domain randomization space helped the network disambiguate between the left and right arms, which appear visually similar, with less training data.

-

Belief map interpretability. Originally, we explored the idea of not training belief maps directly, and instead, let the network learn what belief map representation would be best. For this, we added a softmax layer at the end of the network, and used the keypoint position itself as the training label (instead of the belief map). Sometimes, this yielded intriguing belief maps that appears as if the network was learning an implicit “attention” mechanism. For example, the belief map for the Baxter torso keypoint extended generally around the midsection of Baxter. However, for other cases, the belief maps were not human interpretable, although the detected keypoint position within the belief map was correct. Therefore, we opted to train the network to regress to a particular belief map representation that was inherently interpretable.

Limitations

We hope that DREAM will be useful for roboticists by providing a more efficient approach to camera calibration. However, it is important to specify the current limitations of DREAM.

- DREAM was designed under the assumption that no more than one manipulator would exist in an image. However, DREAM can be extended to multiple manipulators similar to DOPE (where the pose of multiple objects can be estimated).

- DREAM relies on no temporal information — each frame is processed independently. As a result, the result may have some small variance or “jitter” in both two- and three-dimensions. To accommodate use cases where the roboticist knows the camera will not move (e.g., a very secure and rigid camera mounting), DREAM can be used over multiple frames, which will both improve accuracy and reduce jitter.

- Not all detected keypoints are equally useful for solving PnP. Therefore, some robot joint configurations may be more “informative” and robust to missed keypoint detections than others. Furthermore, DREAM will inherit the same limitations of PnP, such as degenerate cases if an insufficient number of keypoints are detected.

Code and Documentation

The DREAM code, including the core library and a ROS node, is available on GitHub. We have also released pre-trained models for the Franka Emika Panda, KUKA iiwa7, and Rethink Robotics Baxter. These models and the datasets we used to quantify our results are also available through the NVIDIA project site.

We highly encourage roboticists to pass on fiducial markers and try our approach the next time you need to calibrate your camera for your vision-based manipulation tasks.

Author

Tim Lee, Ph.D. in Robotics graduate researcher with the Intelligent Autonomous Manipulation Lab at Carnegie Mellon University. Tim completed this research as an intern with NVIDIA’s Seattle Robotics Lab in 2019.

Acknowledgments

We’d like to thank Ankur Handa, Jonathan Tremblay, and Stan Birchfield for their help with editing and proofreading this post.

We’d also like to thank our DREAM coauthors and collaborators — particularly, Jonathan Tremblay and Stan Birchfield – without whom this work would not have been possible. (Teamwork makes the DREAM work!)

Bibliography

Timothy E. Lee, Jonathan Tremblay, Thang To, Jia Cheng, Terry Mosier, Oliver Kroemer, Dieter Fox, and Stan Birchfield. “Camera-to-Robot Pose Estimation from a Single Image.” International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2020.

Jonathan Tremblay, Thang To, Balakumar Sundaralingam, Yu Xiang, Dieter Fox, and Stan Birchfield. “Deep Object Pose Estimation for Semantic Robotic Grasping of Household Objects.” Conference on Robot Learning (CoRL), 2018.

Yu Xiang, Tanner Schmidt, Venkatraman Narayanan, and Dieter Fox. “PoseCNN: A Convolutional Neural Network for 6D Object Pose Estimation in Cluttered Scenes.” Robotics: Science and Systems (RSS), 2018.

Vincent Lepetit, Francesc Moreno-Noguer, and Pascal Fua. “EPnP: An Accurate O(n) Solution to the PnP Problem.” International Journal of Computer Vision (IJCV), Vol. 81, No. 2, 2009.

Tsung-Yi Lin, Michael Maire, Serge Belongie, James Hays, Pietro Perona, Deva Ramanan, Piotr Dollár, C. Lawrence Zitnick. “Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context.” European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2014.

Berk Calli, Arjun Singh, Aaron Walsman, Siddhartha Srinivasa, Pieter Abbeel, and Aaron M. Dollar. “The YCB Object and Model Set: Towards Common Benchmarks for Manipulation Research.” International Conference on Advanced Robotics (ICAR), 2015.