Deep Drone Acrobatics

Acrobatic flight with quadrotors is extremely challenging. Maneuvers such as the loop, matty flip or barrel roll require high thrust and extreme angular accelerations that push the platform to its physical limits. Human drone pilots require many years of practice to safely master such agile maneuvers. Yet, a tiny mistake could make the platform lose control, and brutally crash. This post describes an approach to safely train acrobatic controllers in simulation and deploy them with no fine-tuning (zero-shot transfer) on physical quadrotors. The approach uses only onboard sensing and computation.

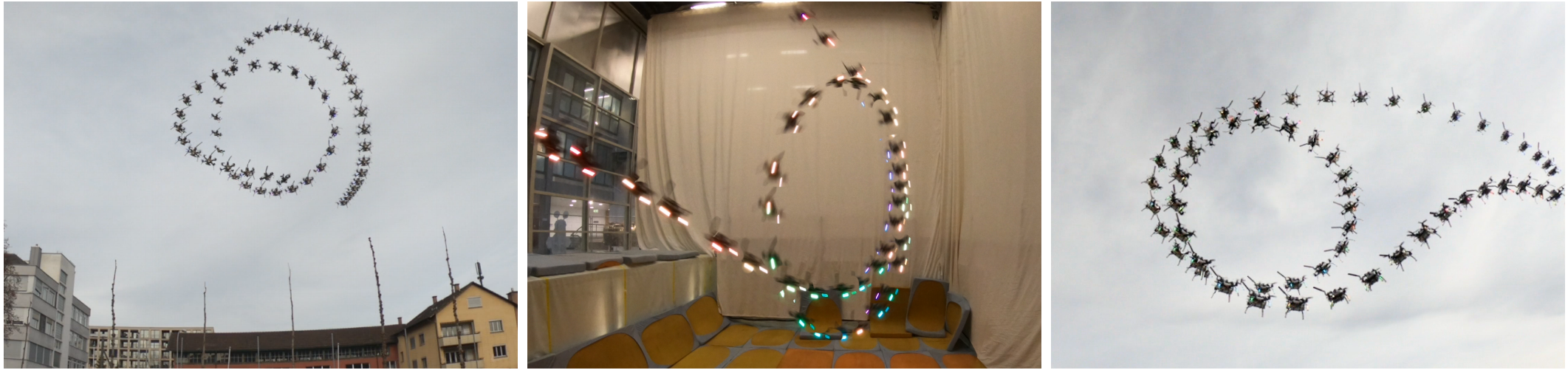

A quadrotor performs a Barrel Roll (left), a Power Loop (middle), and a Matty Flip (right). Paper, Video, Code.

A quadrotor performs a Barrel Roll (left), a Power Loop (middle), and a Matty Flip (right). Paper, Video, Code.

Approach Overview

We train a sensorimotor controller to predict low-level actions from a history of onboard sensor measurements and a user-defined reference trajectory. An observation at time consists of a camera image and an inertial measurement . Since the camera and IMU typically operate at different frequencies, the visual and inertial observations are updated at different rates. The controller’s output is an action that consists of continuous mass-normalized collective thrust and bodyrates . Human drone pilots control drones through this very same interface.

The controller is trained via privileged learning. Specifically, the policy is trained on demonstrations that are provided by a privileged expert: an optimal controller that has access to privileged information that is not available to the sensorimotor student, such as the full ground-truth state of the platform . The privileged expert is based on a classic optimization-based planning and control pipeline that tracks a reference trajectory from the state using Model Predictive Control (MPC).

We collect training demonstrations from the privileged expert in simulation. Training in simulation enables synthesis and use of unlimited training data for any desired trajectory, without putting the physical platform in danger. This includes maneuvers that stretch the abilities of even expert human pilots. To facilitate zero-shot simulation-to-reality transfer, the sensorimotor student does not directly access raw sensor input such as color images. Rather, the sensorimotor controller acts on an abstraction of the input, in the form of feature points extracted via classic computer vision. Such abstraction supports sample-efficient training, generalization, and simulation-to-reality transfer.

The trained sensorimotor student does not rely on any privileged information and can be deployed directly on the physical platform. We deploy the trained controller to perform acrobatic maneuvers in the physical world, with no adaptation required.

Deep Sensorimotor Controller

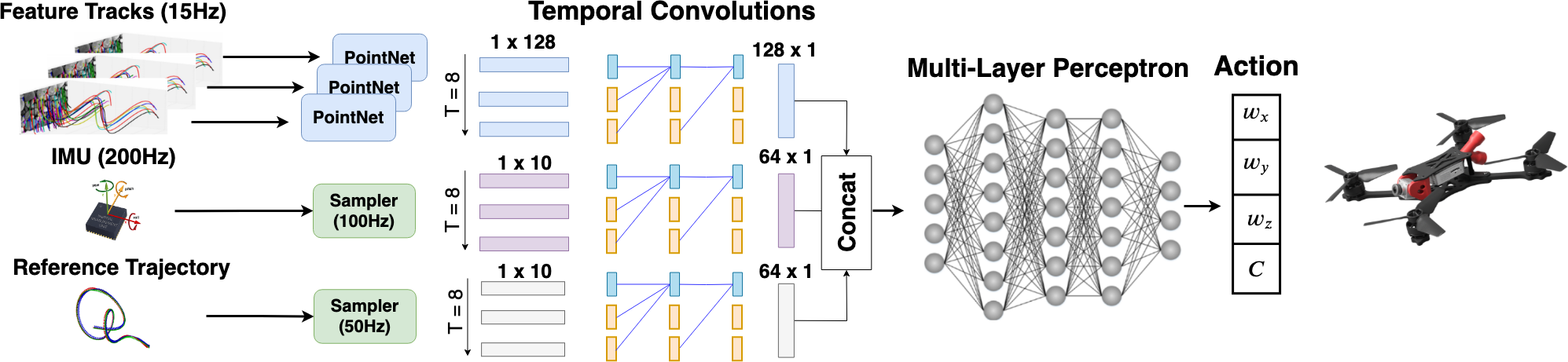

Network architecture. The network receives a history of feature tracks, IMU measurements, and reference trajectories as input. Each input modality is processed using temporal convolutions and updated at different input rates.

Network architecture. The network receives a history of feature tracks, IMU measurements, and reference trajectories as input. Each input modality is processed using temporal convolutions and updated at different input rates.

In contrast to the privileged expert, the deep sensorimotor controller is only provided with onboard sensor measurements from the forward-facing camera and the IMU. There are three main challenges for the controller to tackle: (i) it should keep track of its state based on the provided inputs, akin to a visual-inertial odometry system, (ii) it should be invariant to environments and domains, so as to not require retraining for each scene, and (iii) it should process sensor readings that are provided at different frequencies.

We represent the policy as a neural network that fulfills all of the above requirements. The network consists of three input branches that process visual input, inertial measurements, and the reference trajectory (represented as a time-indexed sequence of desired states), followed by a multi-layer perceptron that produces actions. Similarly to visual-inertial odometry systems, we provide the network with a representation of the platform state by supplying it with a history of length of visual and inertial information.

We account for the different input frequencies by allowing each of the input branches to operate asynchronously. Each branch operates independently from the others by generating an output only when a new input from the sensor arrives. The multi-layer perceptron uses the latest outputs from the asynchronous branches and operates at 100Hz. It outputs control commands at approximately the same rate due to its minimal computational overhead. The output of the neural network is then processed by a low-level controller, which converts the provided thrust and body-rates in rotor commands. While the low-level controller is platform specif and informed about the physics of the drone, the network actions are mostly platform independent.

The network is trained with an off-policy learning approach. We execute the trained policy, collect rollouts, and add them to a dataset. After 30 new rollouts are added, we train for 40 epochs on the entire dataset. This collect-rollouts-and-train procedure is repeated 5 times: there are 150 rollouts in the dataset by the end. We always use the latest available model for collecting rollouts. We execute a student action only if the difference to the expert action is smaller than a threshold to avoid crashes in the early stages of training. The threshold is doubled every 30 rollouts.

Closing the Sim2Real Gap with Abstraction

Training the above controller requires lots of data. Not only is collection of this data with a real robot tedious and expensive, but also challenging. Specifically, the two main challenges are: (i) How to provide perfect state information to a real drone? and (ii) How to protect the platform from damage when a partially trained network is in control? To circumvent these challenges, we train exclusively in simulation. This significantly simplifies the training procedure, but presents a new hurdle: how do we minimize the difference between the sensory input received by the controller in simulation and reality?

Our approach to bridging the gap between simulation and reality is to leverage abstraction. Rather than operating on raw sensory input, our sensorimotor controller operates on an intermediate representation produced by a perception module. This intermediate representation is more consistent across simulation and reality than raw visual input. We formally show that training a network on abstraction of sensory input reduces the gap between simulation and reality. Specifically, using an abstraction function the sim2real gap is strictly lower than training on raw sensory data and upper bounded by (detailed proof in the paper):

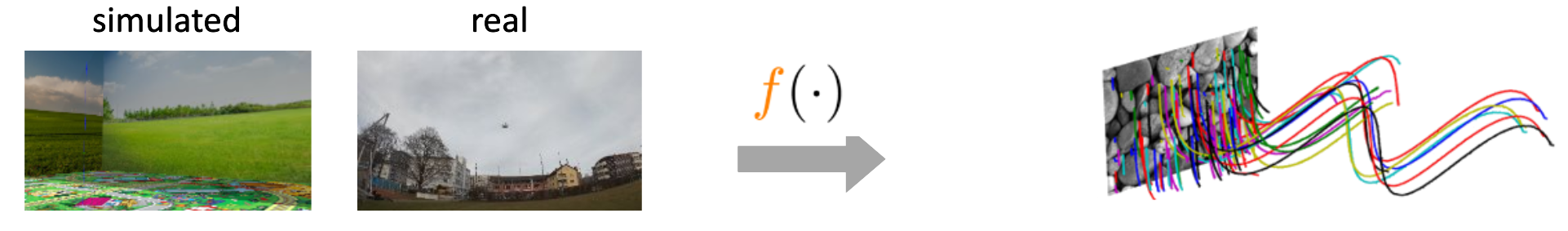

Abstraction function for visual data: Feature tracks extraction.

Abstraction function for visual data: Feature tracks extraction.

The mapping is task-dependent and is generally designed with domain knowledge to contain sufficient information to solve the task while being invariant to nuisance factors. In our case, we use feature tracks as an abstraction of camera frames. The feature tracks are provided by a visual-inertial odometry (VIO) system. Thanks to this abstraction, we do not require any randomization of the geometry and appearance of the scene during data collection. In contrast to camera frames, feature tracks primarily depend on scene geometry, rather than surface appearance. We also make inertial measurements independent of environmental conditions, such as temperature and pressure, by integration and de-biasing.

Main Experimental Findings

The Longer The Maneuver, The More Important The Role Of Visual Information.

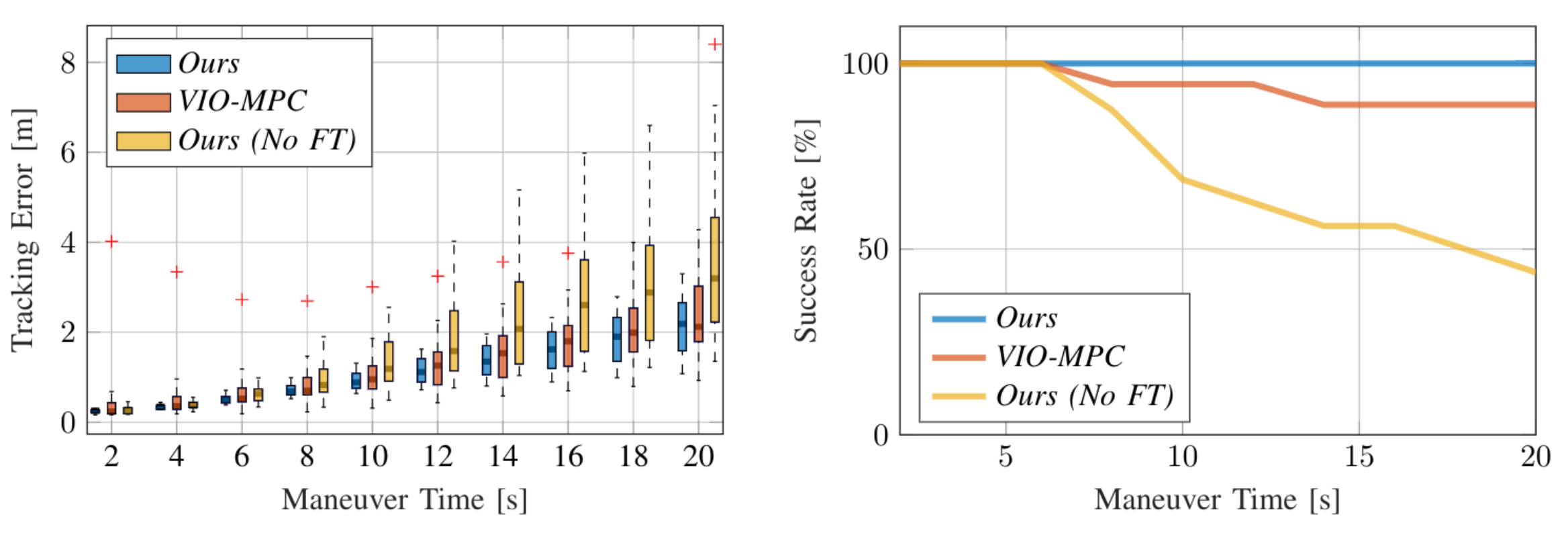

Our experimental evaluation reveals that for very short maneuvers (up to 6 seconds) IMU measurements were sufficient for acrobatic flight. However, for longer flight duration, visual information was necessary to successfully address the IMU drift and complete the maneuver. Indeed, visual information reduces the odds of a crash by up to 30% in the longest maneuvers.

Our neural controller outperforms the classic pipeline based on estimation and control (VIO-MPC). For long maneuvers, visual information are necessary to reduce drift and complete the maneuver without crashing.

Our neural controller outperforms the classic pipeline based on estimation and control (VIO-MPC). For long maneuvers, visual information are necessary to reduce drift and complete the maneuver without crashing.

Interestingly, the neural network learns to find a balance between feature tracks and inertial measurements. Indeed, when looking at images with low features (for example when the camera points to the sky), the neural net will mainly rely on IMU. When more features are available, the network uses them to correct the accumulated drift of the IMU.

On all maneuvers, we outperform the tradition pipeline of state-estimation and control (VIO-MPC) in term of tracking error and odds of a crash.

Abstraction Favours Both Training and Generalization

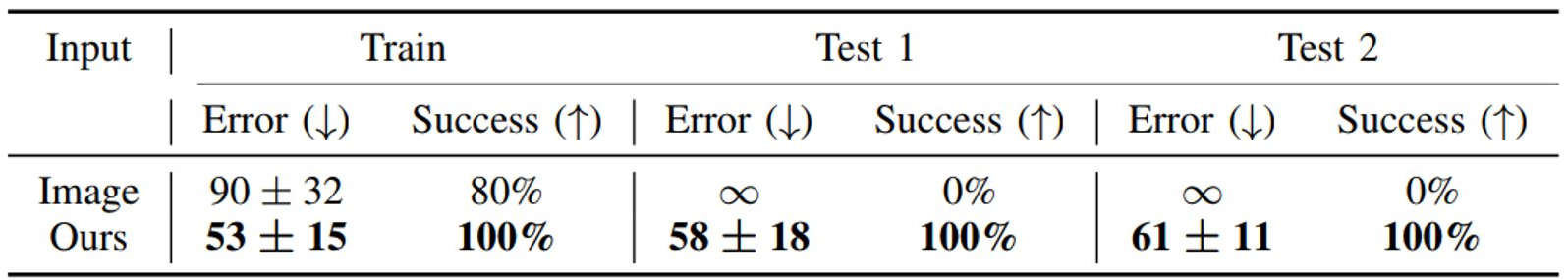

To validate the importance of input abstraction, we compare our approach to a network that uses raw camera images instead of feature tracks as visual input. We then compare the results of this naive approach with our proposed abstraction procedure.

Training on feature tracks instead of raw images enables efficient training and generalization to scenes with novel appearance

Training on feature tracks instead of raw images enables efficient training and generalization to scenes with novel appearance

In the training environment, the image-based network has a success rate of only 80%, with a 58% higher tracking error than the controller that receives an abstraction of the visual input in the form of feature tracks (Ours). Even more dramatically, the image-based controller fails completely when tested with previously unseen background images (Test 1, Test 2). In contrast, our approach maintains a 100% success rate in these conditions.

Acrobatic Flight on a Real Quadrotor

Below is a short clip demonstrating our controller flying a power loop on physical drone. We learn sensorimotor policies for three acrobatic maneuvers that are popular among professional drone pilots: the power loop, the barrel roll, and the matty flip. These trajectories contain high accelerations and fast angular velocities around the body axes of the platform. All maneuvers start and end in the hover condition.

Check out the full video of the paper for watching our quadrotor perform the other maneuvers in both indoor and outdoor environments.

Limitations

Deep Drone Acrobatics proposed a totally novel controller structure which merges the classic estimation module with the control module in a single, specialized, sensorimotor controller. The approach outperforms the traditional method of separation between estimation plus control, but it comes with some limitations. We see these limitations as a very interesting venue for future work.

- The neural controller is maneuver specif, i.e. each maneuver requires a specifically trained controller.

- Maneuver duration is always relatively short (around 20 seconds). This is fine for acrobatics, but what if we want to track longer trajectories, as in drone racing?

- Each maneuver is assumed to be obstacle-free. What if there are some obstacles on the way?

Code

Deep Drone Acrobatics comes with open-source code, available on GitHub. You can use this code to train your controller on ours acrobatic maneuvers, but also on any other maneuver you wish. Pay attention when deploying the controller on a real platform: drones flying at high speed should be treated with the appropriate care!

Authors

The post was written by Antonio Loquercio and Elia Kaufmann, both Ph.D. students in Robotics with the Robotics and Perception Group at the University and ETH Zurich. This research was developed in the context of a collaboration with the Intel Network of Intelligent Systems.

Acknowledgments

We’d like to thank Ankur Handa for their help with editing and proofreading this post.

We’d also like to thank our coauthors and collaborators without whom this work would not have been possible.

Citing

@article{kaufmann2020RSS,

title={Deep Drone Acrobatics},

author={Elia Kaufmann, Antonio Loquercio, René Ranftl, Matthias Müller, Vladlen Koltun, Davide Scaramuzza},

journal={RSS: Robotics, Science, and Systems},

year={2020},

publisher={IEEE}

}