Part I: Indexing Datasets of 3D Indoor Objects

This is the first part of a series of posts on consolidating datasets of 3D objects and scenes. In this post, we will focus on datasets of 3D objects. This is a modest attempt at covering the breadth of such datasets that have been developed and released over the past decade and a half. These datasets have been particularly helpful in simulations-to-real world transfer in robotics, object detection, 6 DoF object pose estimation and spatial 3D understanding in computer vision and SLAM. Therefore, we believe it is important to index such datasets and understand their strengths and limitations as well as the future of such datasets going forward.

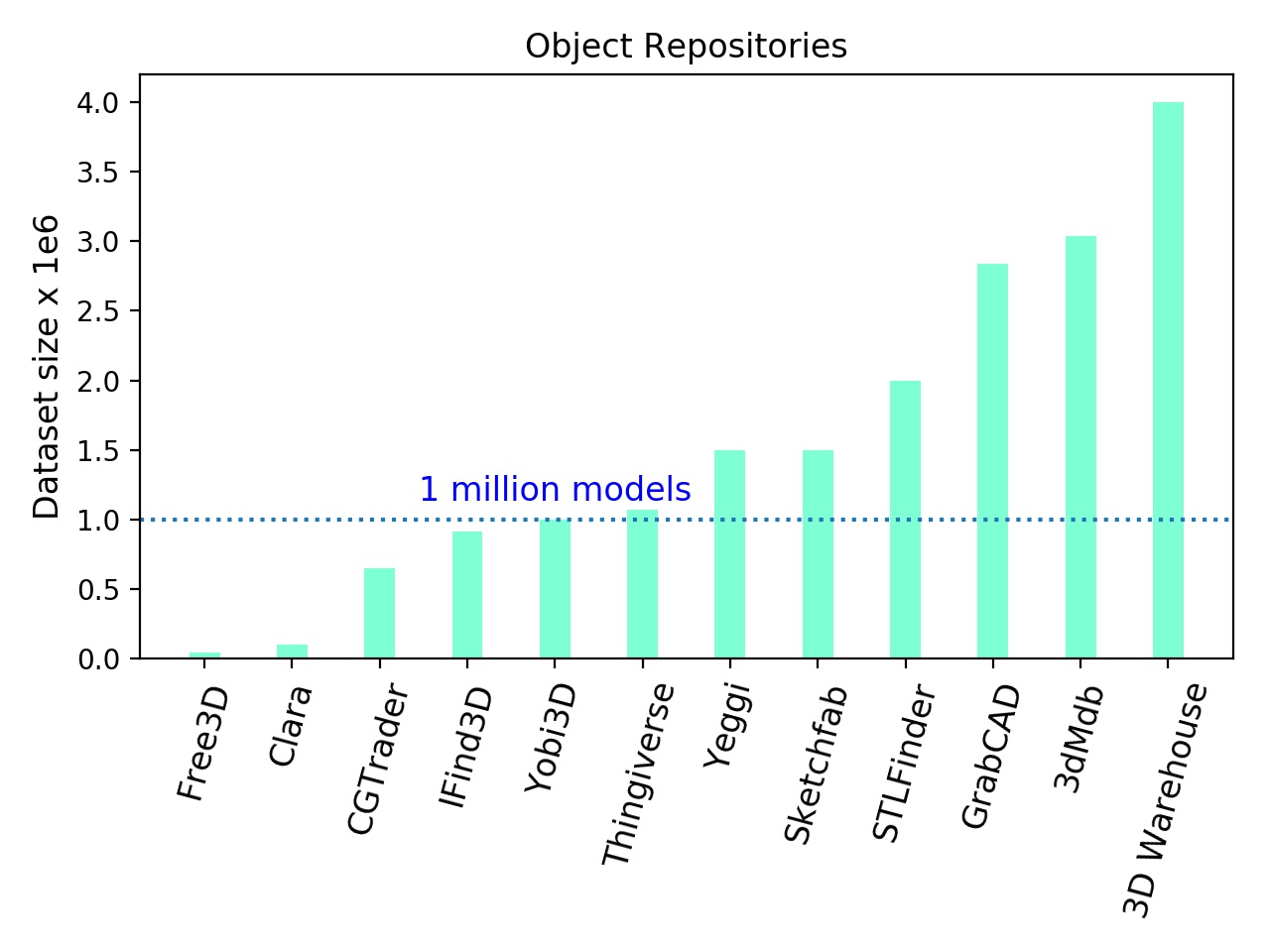

The datasets have been curated either via synthesising 3D models using a 3D design software or scanning real world 3D objects from multiple views with RGB as well as depth cameras. Historically, researchers in computer vision and graphics have maintained a particular interest in 3D shape modelling and understanding and therefore contributed to the growth and evolution of these datasets. Although, there have been attempts at curating datasets by the game development community but they have remained within the confines of the community and have largely not been publicly shared or released for free. It is worth mentioning that today various companies and websites (the list below only mentions a few popular ones and is by no means exhaustive) allow creating, sharing and searching 3D models e.g.

- Onshape have a large repository of CAD models that are freely available for research purposes. They are a cloud based service for designing and sharing CAD models.

- 3DWarehouse maintain a large collection of 3D models created in sketchup and also provide a search engine for these. The 3D models can be downloaded for free.

- IgnitionFuel provides free 356 3D models with URDF, SDFs (Signed Distance Functions) as well as parameters to simulate kinematics and dynamics.

- Clara, like onshape is a cloud based 3D content creation software and provides many 3D models for free.

- Yobi3D allows searching 3D models and provide links to the corresponding website where those models can be available. Not all of them are for free.

- Unity Asset Store provide 3D models that can be used within the Unity3D engine. High quality assets tend to require licensing and not available free of charge.

- Kujiale, an indoor design platform in China that provides 3D indoor objects as well scenes but the majority of them require licensing and are not available for free.

It is important to note that even though these models are freely available, most commercial companies cannot simply use them. In most cases, special agreements have to be made via appropriate legal channels and departments. Therefore, it is worthwhile spending time reading the license agreement file for any terms and conditions that may come with the dataset.

The image above shows the size of repositories that provide 3D assets and models. We observed that large majority of these repositories today contain 1M models and we believe the content (either designed by artists or automatically generated) will continue to grow with time.

Next, we give a brief overview of various data formats that synthetic/real-world models are released in. These are the basic formats that have been around for a long while and it is worth understanding how these 3D models are stored and shared publicly.

Data formats

CAD models

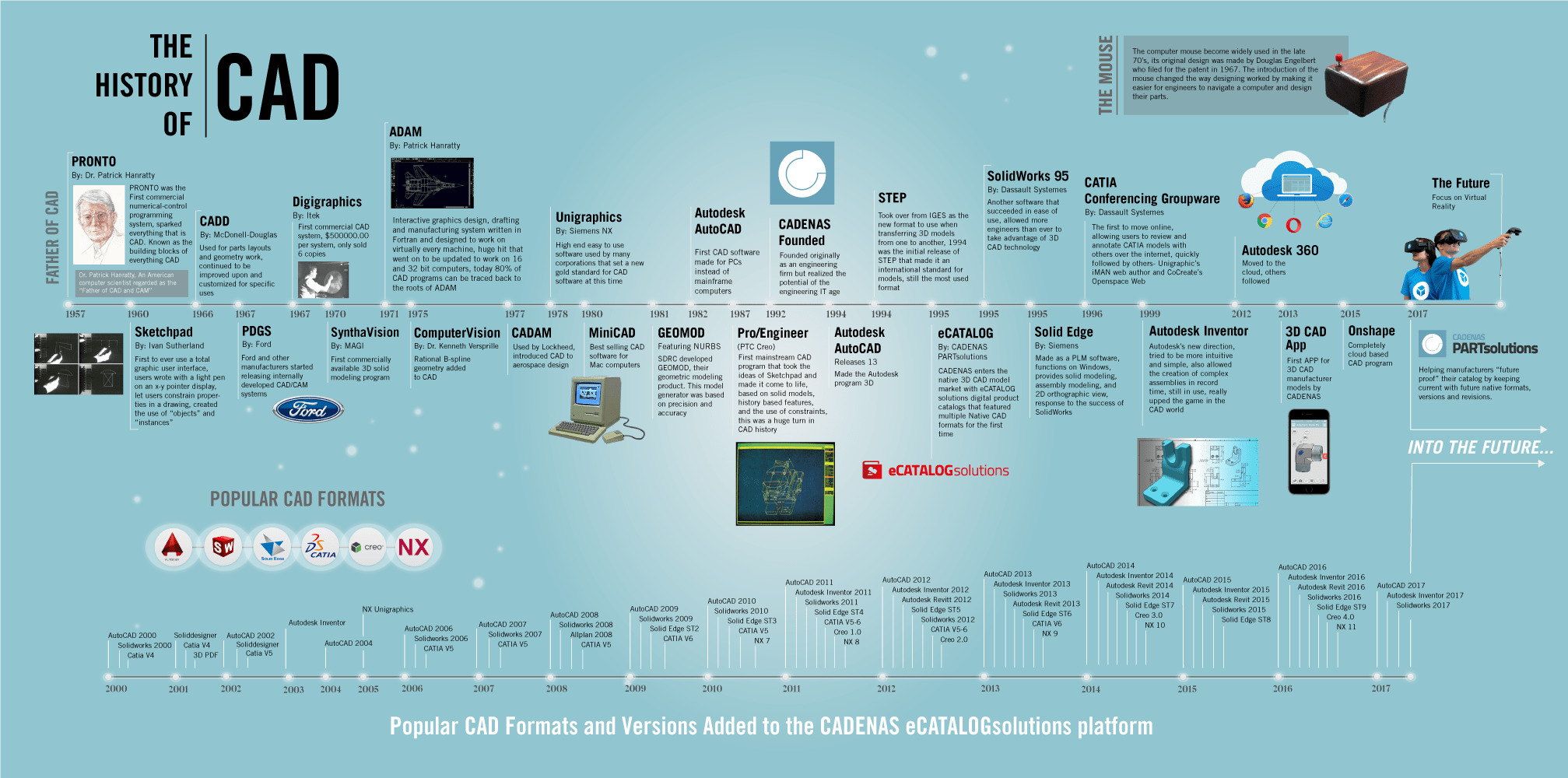

CAD design and modelling have a long history of enabling creation of 3D models of complicated objects on a computer. This has been extremely powerful in manufacturing, design and architectures of building and bridges. From the early days of revolutionary Sketchpad to today’s cloud services for design, CAD modelling has evolved immensely.

CAD allows engineers and designers to build realistic computer models of parts and assemblies. These models can then be 3D Printed or CNC machined as well as used to run complex simulations. A wide range of parameters can be simulated such as strength or temperature resistance before any physical models have been created, enabling a much faster and cheaper workflow.

The origins of CAD design can be traced back to three separate sources, highlighting the services CAD systems can be employed in. The first of these sources has its origins in automating the drafting process pioneered by the General Motors Research Laboratories in the early 1960s. One of the important time-saving advantages of computer modeling over traditional drafting methods is that the former can be quickly corrected or manipulated by changing a model’s parameters. The second source of CAD was in the testing of designs by simulation. The use of computer modeling to test products was pioneered by high-tech industries like aerospace and semiconductors. The third source of CAD development resulted from efforts to facilitate the flow from the design process to the manufacturing process using numerical control (NC) technologies, which enjoyed widespread use in many applications by the mid-1960s.

The origins of CAD design can be traced back to three separate sources, highlighting the services CAD systems can be employed in. The first of these sources has its origins in automating the drafting process pioneered by the General Motors Research Laboratories in the early 1960s. One of the important time-saving advantages of computer modeling over traditional drafting methods is that the former can be quickly corrected or manipulated by changing a model’s parameters. The second source of CAD was in the testing of designs by simulation. The use of computer modeling to test products was pioneered by high-tech industries like aerospace and semiconductors. The third source of CAD development resulted from efforts to facilitate the flow from the design process to the manufacturing process using numerical control (NC) technologies, which enjoyed widespread use in many applications by the mid-1960s.

Similar to vector graphics for images, this representations allows resampling the surface data at arbitrary resolutions, with or without connectivity information (i.e. into a point cloud or a mesh). In the animation above, an object being manipulated in a CAD program is shown where each of the edits results in changing of the shape of the object. These edits to tend to be described by a parametric surface. As can be seen in the Wikipedia there exists a huge number of CAD formats. The most commonly used representations tend to be based on the topology (faces, edges and vertices) as well as their geometry (surfaces, curves and points) with primitive shapes of the form of cones, planes, cylinders, spheres or curves like NURBS, circles and ellipses. These representations can be converted to meshes with 3D finite element mesh generators like GMSH.

STL format

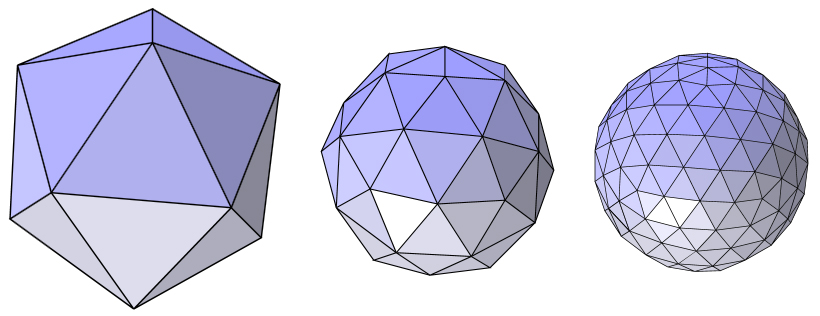

The format only describes the 3D surface geometry of the object i.e. information about 3D vertices and normals is provided and no information of colour, texture or other possible meta-data relevant for the model is included. These files are usually generated by a CAD program and are most commonly used in the 3D printing. They store the 3D information using a concept called “tessellation” where a primitive shape (e.g. a triangle described by three vertices and a normal) is repeated across to encode the surface geometry without overlaps and gaps. The format was invented by the Albert Consulting Group for 3D systems, a company co-founded by Chuck Hull, in 1987. Chuck had then invented stereolithographic 3D printer and his company were looking for a way to transfer the information from 3D CAD models to the printer and realised they could use the concept of “tessellation” to describe the geometry. For instance, the image below shows different levels of tessellation of sphere done with a triangle.

STL files come in two different flavours namely ASCII and Binary and contain descriptions of 3 vertex facets including their normals. The main restriction placed upon the facets in STL files is that all adjacent facets must share two common vertices.

OBJ format

The OBJ format was created by Wavefront Technologies to store lines, polygons, and free-form curves and objects. Similar to STL it stores the surface geometry but unlike STL it also stores the colour and texture information. OBJ format can approximate surface geometry without blowing up the size of the model using bezier curves or NURBS. There are multiple ways to store the geometry with OBJ format. In its simplest form, OBJ allows tessellation of the geometry in the form of triangles, quadrilaterals or more complex polygons. The vertices and normals of the polygons are stored to encode the geometry. Other ways to encode geometry with OBJ include free-form curves like bezier curves and free-form surfaces like NURBS. Free-form surfaces are more precise and they lead to smaller file sizes at higher precision compared to other methods. Although STL remains the most popular format for 3D printing, the size of the file very quickly increases for high-resolution 3D models and the lack of colour information makes it somewhat restrictive and therefore OBJ has been slowly gaining popularity.

Other Formats

In addition to the STL/OBJ formats, it is worth mentioning that most articulated objects in robotics come in URDF (Unified Robot Description Format) format. This format describes both the collision shapes as well as limits of various joints and links that the articulated may have. The figure on the left shows a robot with various joints and links animated. In addition to URDF, COLLADA (DAE) also allows articulated kinematics and dynamics but due to complexities involved in handling and managing the format, it is not very popular.

While there are lots of publicly available datasets for passive objects in the form of STL/OBJ format there are no datasets that have been widely used for benchmarking with URDF format. However, for various tasks involving robot kinematics and dynamics URDF is the most popular format.

In addition to the STL/OBJ formats, it is worth mentioning that most articulated objects in robotics come in URDF (Unified Robot Description Format) format. This format describes both the collision shapes as well as limits of various joints and links that the articulated may have. The figure on the left shows a robot with various joints and links animated. In addition to URDF, COLLADA (DAE) also allows articulated kinematics and dynamics but due to complexities involved in handling and managing the format, it is not very popular.

While there are lots of publicly available datasets for passive objects in the form of STL/OBJ format there are no datasets that have been widely used for benchmarking with URDF format. However, for various tasks involving robot kinematics and dynamics URDF is the most popular format.

Synthetic Datasets

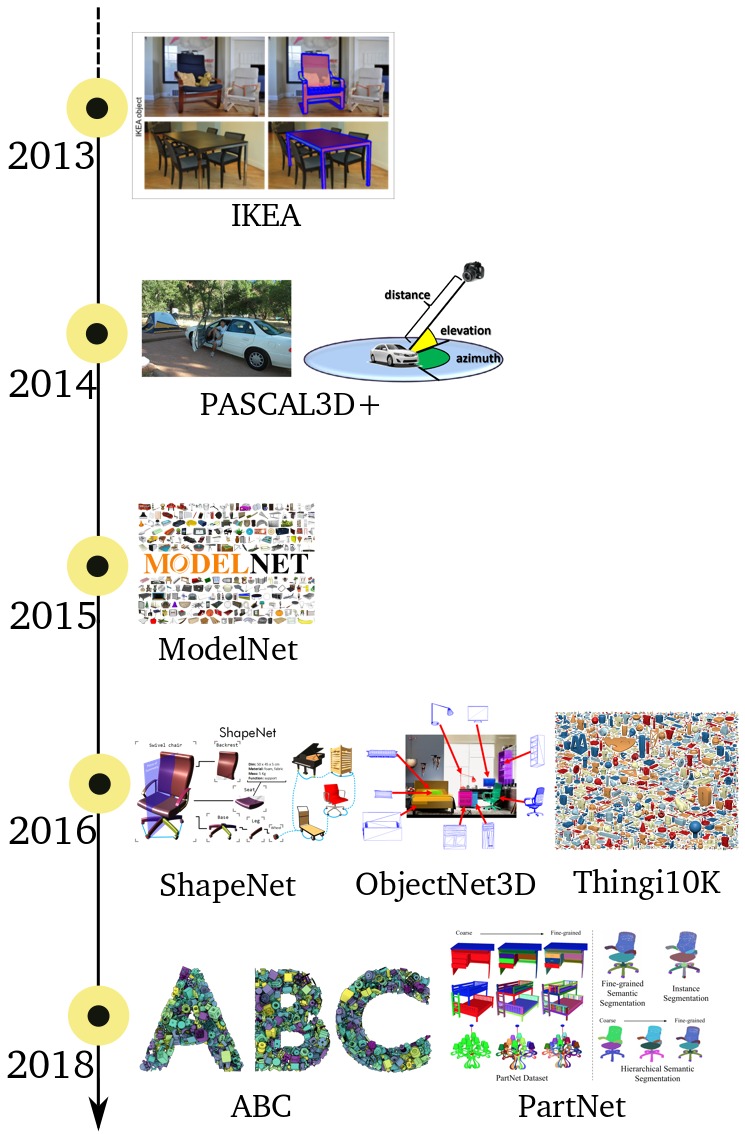

Synthetic object datasets have remained popular particularly among researchers in computer vision and graphics since the early 2000s. We have listed some of the popular datasets since 2003 until 2018 in the table below.

Note that some of the links in the table may be outdated now but we added them anyway as this is where the datasets were uploaded first.

We observed that both graphics and vision researchers have focussed either on the geometry (in the form of meshes and point clouds) or variation among the classes of shapes but very little about their use within physics engines for control. Therefore, until recently, most datasets did not provide any articulation information (hinges or joints) of the objects and their parts.

We refer to articulations as kinematic constraints in the form of hinges and joints. They are useful in animating a particular object in a physics engine.

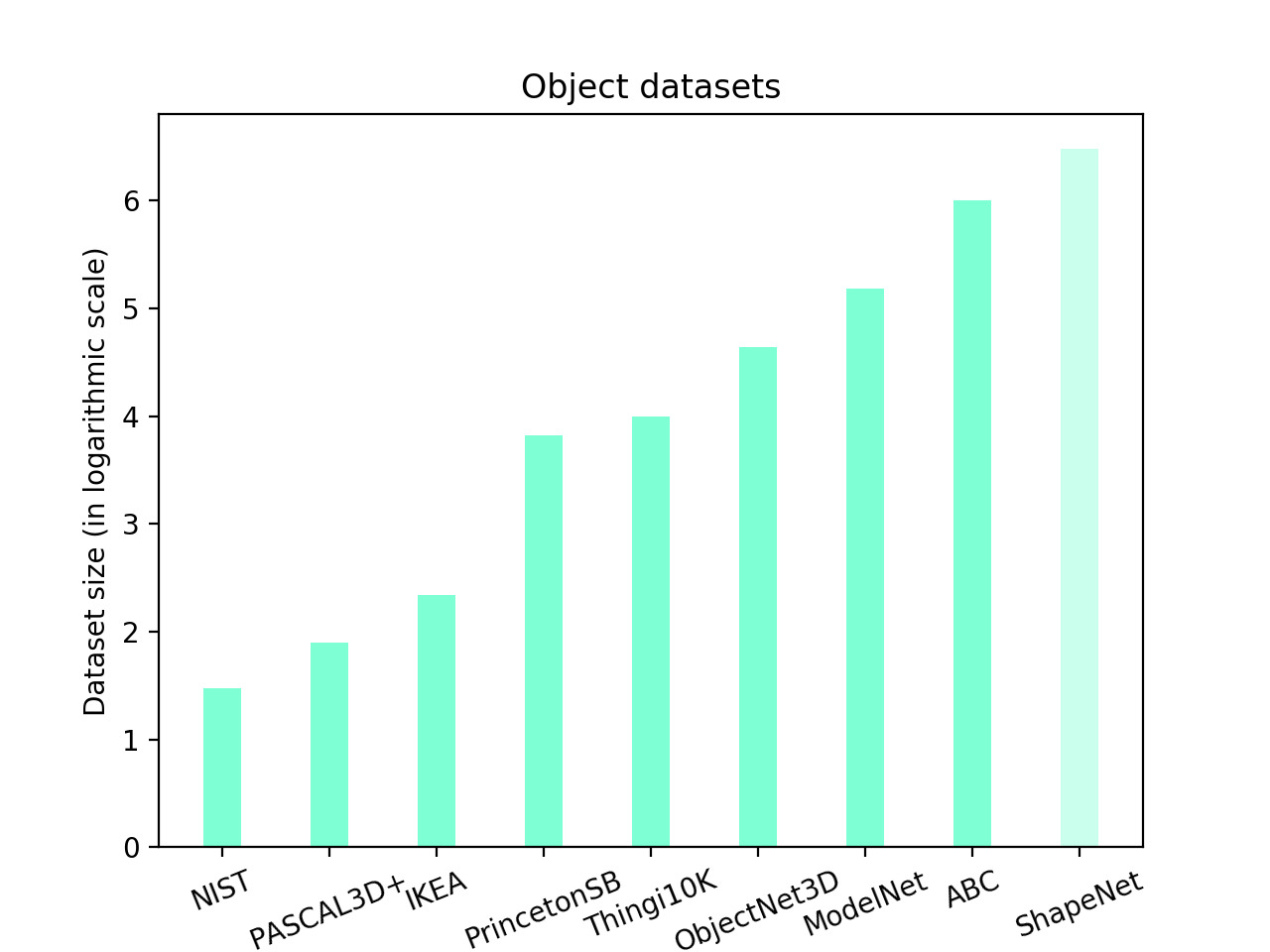

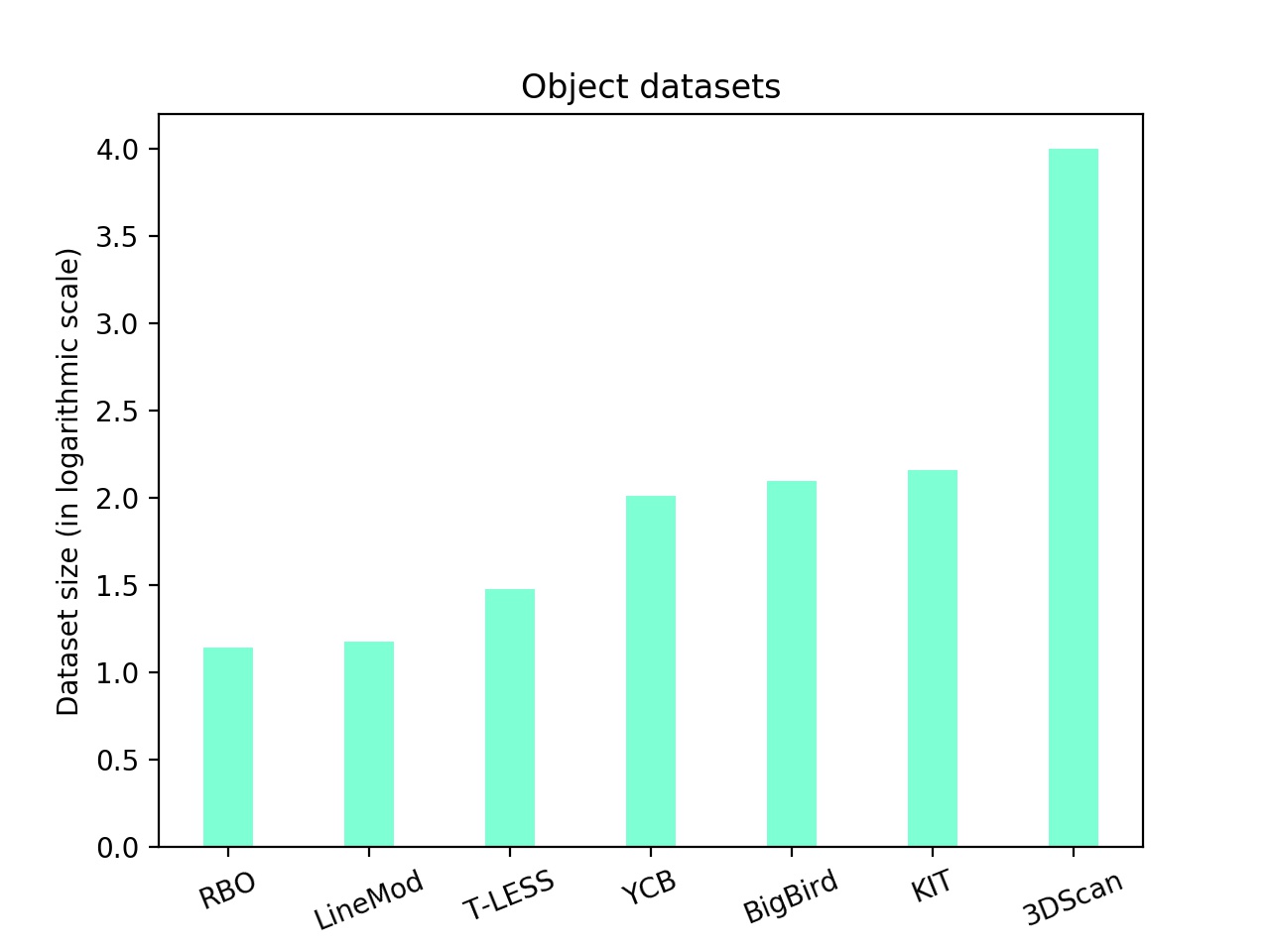

Moreover, we have observed that the sizes of publicly available datasets of synthetic 3D objects show a linear increase of ~10 when ranked on a logarithmic scale. The rising interest in these datasets has been driven particulary by the researchers working on deep learning that can handle and indeed require large amount of data. We also observe that most of the researchers have focussed on a particular set of 3D objects e.g. chairs, tables and sofas.

It is worth emphasising that

- Although ShapeNet contains 3M models, only ~57K models have been cleaned and released publicly. Hence a lighter colour on the ShapeNet bar in the graph.

- PartNet builds on top of ShapeNet and adds hierarchical part based annotations and provides object articulation information that could be useful in virtual environments for robot learning.

- ObjectNet3D uses a large fraction of models from ShapeNet in addition to the ones mined from the 3DWarehouse.

- The ABC dataset is not publicly available yet (at the time of writing this post). The majority of the models are mechanical parts and not typical categories of objects like chairs, tables etc.

Besides the datasets shown above, we would also like to mention the popular Dex-Net 1.0 dataset which is composed of 13,252 3D mesh models collected from assorted mix of various synthetic as well as real world datasets: 8,987 from the SHREC 2014 challenge dataset, 2,539 from ModelNet40, 1,371 from 3DNet, 129 from the KIT object database, 120 from BigBIRD and 80 from the YCB dataset.

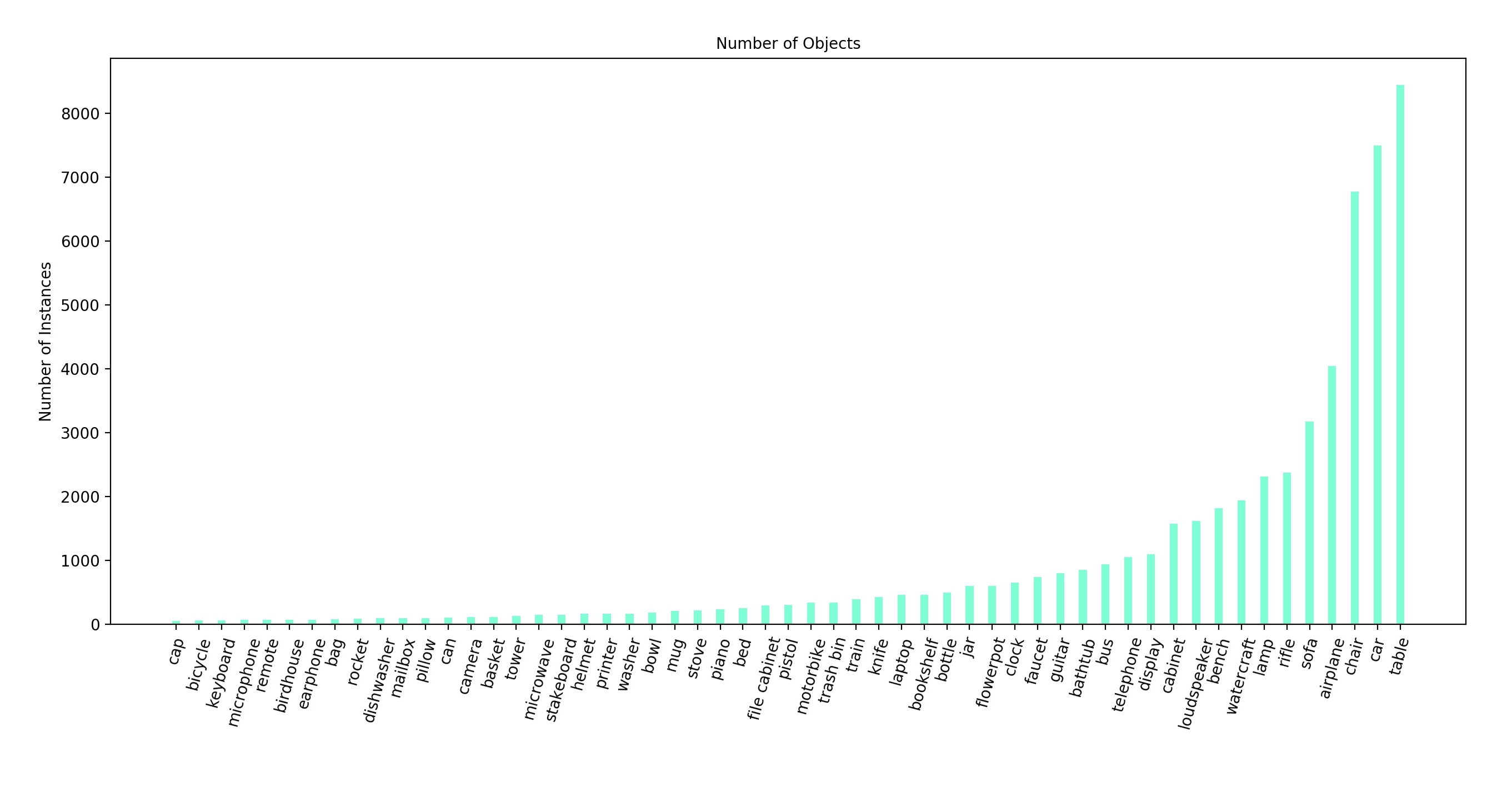

Importantly, we note that most datasets tend to have huge class imbalance among various categories. The image below shows the breakdown of ShapeNetCore (part of ShapeNet) that has ~57K models — the biggest publicly released 3D model dataset as of yet. As we can see, it has large number of models for categories like chairs, tables, sofas, cabinets but relatively few for bed, bowl and can.

Overall, datasets like ModelNet and ShapeNet have been extremely valuable in computer vision and robotics. For instance, ModelNet has been used for 3D object detection from 3D voxel grids in VoxNet and OctNet, from raw point cloud in PointNet and PointNet++ while ShapeNet has been particularly useful in benchmarking robotic grasping. The popular DexNet has evolved over the years benchmarking grasping using models from ShapeNet. The work of Bousmalis et al., Tobin et al. and recently James et al. have all trained large scale models on grasping using freely available ShapeNet models.

Challenges of curating a synthetic dataset

Curating a large scale synthetic dataset can be an extremely labourious endeavour. Even if the objects are publicly available there are still a lot of challenges involved

- Manual Filtering: Publicly available 3D models tend to require lot of manual filtering e.g. some 3D models have duplicate vertices and normals, duplicate and sometimes contradicting normals for the same face or broken 3D models to name a few. Mitsuba-ShapeNet and SceneNet RGB-D have written custom rendering shaders to bypass the rendering issues that come with 3D models with duplicate vertices and normals. Additionally, some 3D models come with two separate meshes and require stitching.

- Lack of Textures: Some 3D models have missing textures or lack material information. For instance, some objects have the path of material information set to the path on the local computer of the designer and this sometimes results in missing texture information. Additionally, the UV-mapping of the vertices tends to be wrong at times resulting in unexpected wrapping of texture on the mesh.

- Unfinished Models: Most beginners working on websites that offer cloud services to create 3D models tend to leave their basic or unfinished models in the online shared repositories. Therefore, unless you download and go through the models it is hard to filter them out.

- Lack of Scale Information: Various hobbyists and beginners also create 3D models that do not come with metric information. This requires scaling them back to metric units so they are physically meaningful.

- Canonical Reference Frame: It is also important to have all the models registered in a canonical reference frame so they can be arbitrarily rotated if needed for any future purposes. However, this is not always the case.

- Collision Shapes: If these models are to be used in physics engines or bounding box collisions detection, they require collision shapes (generally a convex hull or convex decomposition of the mesh). Therefore, they require additional processing with external softwares like V-HACD to decompose the mesh into piecewise convex meshes. Despite this, sometimes a lot of manual work is needed on top of this because the automatically generated convex decomposition by a program is not very good.

- Skeletonisation: Meshes that have dense point clouds require skeletonisation as rendering time increases proportionally with the number of 3D points.

Real World Datasets

The curation of real world datasets (i.e. scans of real-world objects) has been only recent in the computer vision and robotics community. This has been made possible by either offline multi-view stereo methods (e.g. a more commonly used term in computer vision and SLAM literature is Bundle Adjustment) or online real-time 3D reconstruction (e.g. Curless and Levoy inspired methods that use depth cameras to turn the live feed into a 3D model like KinectFusion)

Since both methods tend to optimise a non-linear cost function by first linearising via taylor series expansion, these methods tend to be quite brittle and have a tendency to break catastrophically at times leading to a painful process of redoing the reconstruction from scratch. Therefore, extra care must be taken to ensure that process is smooth.

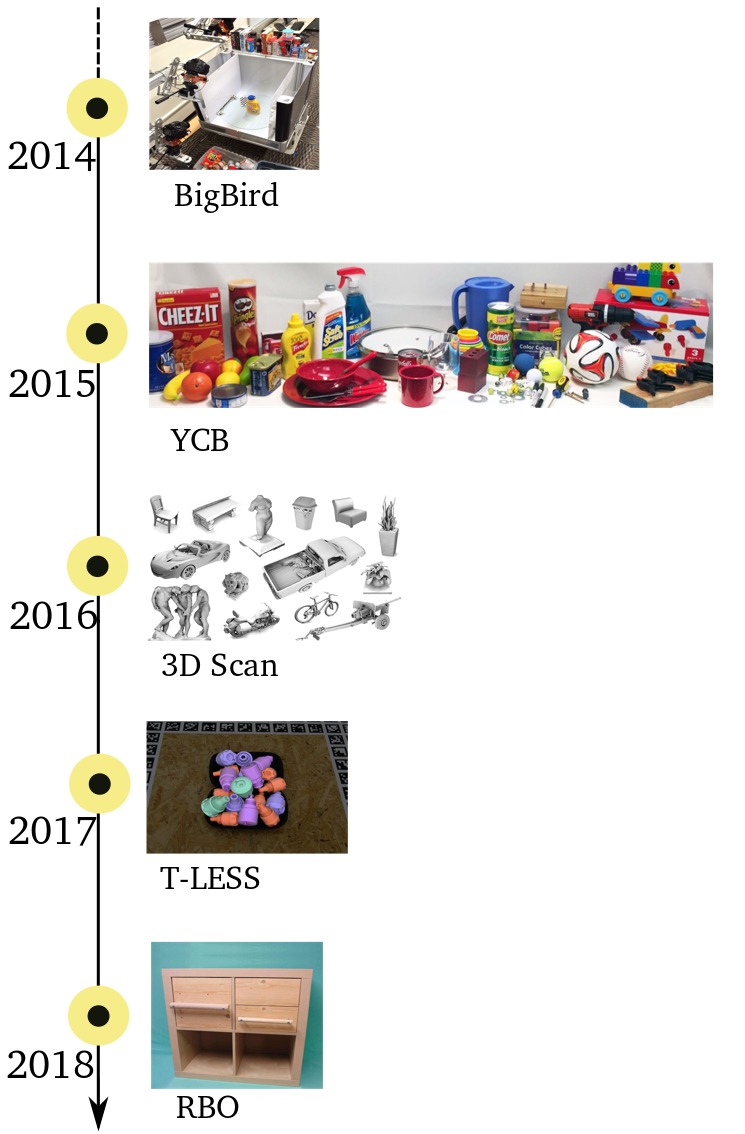

| Dataset | Year | Articulations | Source Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| B3DO | 2011 | http://kinectdata.com/ | |

| RGB-D Object Dataset | 2011 | http://rgbd-dataset.cs.washington.edu/index.html | |

| KIT | 2012 | https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0278364912445831 | |

| LINEMOD | 2012 | http://campar.in.tum.de/Main/StefanHinterstoisser | |

| BigBird | 2014 | http://rll.berkeley.edu/bigbird/ | |

| YCB | 2015 | http://www.ycbbenchmarks.com/ | |

| 3DScan | 2016 | http://redwood-data.org/3dscan/ | |

| T-LESS | 2017 | http://cmp.felk.cvut.cz/t-less/ | |

| RBO | 2018 | https://tu-rbo.github.io/articulated-objects/ |

It is worth noting that

- Since most of these datasets require setting up a rig and scanning the whole process tends to be quite labour intensive therefore, these datasets tend to be quite small in size.

- The RBO dataset is the smallest but has the articulation information that allows it to be animated kinematically in physics engines.

- The T-LESS dataset provides 30 3D models for textureless objects.

- The most popular YCB object dataset though provides ~100 3D object models scanned by a reconstruction system but not all the 3D models are clean and some of them tend to have missing texture information or textures tend to be quite blurry.

These datasets have been primarily useful for 6 DoF pose estimation of objects in real world e.g. LineMod, PoseCNN, DenseFusion all employ various stages to detect and track the pose of the object in 3D. The 6-DoF pose of an object is basic extrinsic property of the object which the robotics community also calls as state estimation. These datasets in essence help answer the what and where questions about the object in the real-world scene. Importantly, this is perhaps one step towards turning our real world into a simulated model (real-to-sim) by constantly keeping a copy in simulation and updating the locations and orientations of the 3D objects as done in Kim et al., Fisher et al. or SLAM++.

In the animation below, we show YCB scanned real-world objects used inside the PyBullet physics simulator.

For physics simulation, articulations in the form of hinges and joints as well as collisions shapes of objects in the form of bounding volumes etc. are important.

Challenges of curating real world dataset

- Scalability: Collecting large scale real world data is extremely labour intensive. There have been attempts to collect large-scale data via crowdsourcing in the past e.g. Kinect@Home but these have unfortunately been unsuccessful.

- Watertight 3D Models: Scanning watertight models can be extremely tricky if the model has kinematic joints and dynamics involved with them, or the object is resting against another where reaching a certain part of the object is not possible without moving the object. This process is extremely hard to automate.

- Blurry Textures: This is quite common with 3D reconstruction methods where various image observations are averaged from multiple views leading to blurry and crummy textures. Most of these methods tend to use a slightly simplistic lambertian surface approximation which means that the texture from different viewpoints does not change. Therefore, there is no proper handling of specular, shiny and reflective surfaces and threfore when pixel intensities are registered from multiple viewpoints on a given 3D location they tend to average out leading to blurry textures. There are some solutions to that but the errors due to lambertian surface assumption means that a full light-field estimation is required and that is also very cumbersome.

- Calibration Rigs: Most of the scanning requires setting up multiple cameras or a person going around the object to obtain multiple views and registering them in one reference frame, camera calibration and constrained set-up where the object is placed. Any slight changes to the set-up may require calibration without which the registration errors quickly compound.

What should an ideal object dataset look like then?

- Large Variety: Should contain large variety of objects and intra-class variability. The dataset should also aim to have uniform distribution of all kinds of classes to avoid any bias towards a particular set.

- Synthetic: Preferably synthetic as collecting water-tight models of real world objects still remains very challenging. Not because it requires labourious scanning of the object from multiple views but it requires the intent of the reconstruction to be conveyed to the robot or user. This is more relevant when scanning objects that have hinges and joints e.g. one needs to open the cabinet (the intent here is to open) to see what is inside and how to scan it and ensure that the scans are registered appropriately with the previously collected ones. Scanning what is behind the object is also difficult. Therefore, synthetic object models will likely be essential to sidestep these problems.

- CAD Format: Preferably CAD models so they can be sampled at arbitrary resolution without any loss of data. They are metrically accurate and can be converted to STL or OBJ format (vice-versa is lossy). Additionally, if you are stitching different CAD models together the relative rotation and translation can be easily obtained via a CAD software. This avoids the calibration/registration process that one has to do on the real world data. Furthermore, they can be 3D printed and therefore provide a perfect simulation to real world match of the 3D model.

- Physics Parameters: Should come with various object intrinsic properties like collision shapes, physical properties (e.g. friction, center of mass, inertia) as well as articulation information so they can be used directly into a physics engine. If properties like friction, mass, inertia etc. are not provided there are certainly ways to estimate them via analysis-by-synthesis approaches or calibrating the simulator to the real world with particle filters. However, it is also possible that this calibration process might yield parameters that are optimal given the objective function but not necessarily physically meaningful.

We note that despite the availability of these large scale datasets, artists and designers are needed to create bespoke 3D object models and assets — a term often called content creation. This is time consuming and requires multiple iterations between the client and the designer.

Authors

Ankur Handa, Andrey Kurenkov and Miles Brundage

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Erwin Coumans, Arsha Nagrani, Kai Arulkumaran, Andrei Bursuc, Matthias Plappert, James Davidson, Chris Paxton, Balakumar Sundaralingam, Avital Oliver, Fei Xia, Jacky Liang, Feryal Behbahani, Joe Watson, Karl Van Wyk, Aaron Walsman, Clemens Eppner, Stephen James, Josh Tobin, Denny Britz and Pranav Shyam for proofreading and suggestions.

Credits

- The CAD history image is obtained from https://partsolutions.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/The-history-of-CAD_CADENAS_R3.png.

- The STL tessellation image is obtained from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7476233.

- The ShapeNet object breakdown can be found here http://shapenet.cs.stanford.edu/shapenet/obj-zip/ShapeNetCore.v2-old/shapenet/tex/TechnicalReport/main.pdf.

- The content about ShapeNet is obtained from the ShapeNet doc http://shapenet.cs.stanford.edu/shapenet/obj-zip/ShapeNetCore.v2-old/shapenet/tex/2016Proposal/2016shapenet_main.pdf.

- The numbers in the plot on 3D models offered by various online repositories are obtained from https://www.aniwaa.com/best-sites-download-free-stl-files-3d-models-and-3d-printable-files-3d-printing/ and https://3dprintingforbeginners.com/3d-model-repositories/.

- The URDF robot image is obtained from https://gkjohnson.github.io/urdf-loaders/unity/Assets/URDF-Loader/.